A few years back, Lebanese singer-songwriter

Yasmine Hamdan made a splash in a scene-stealing moment of

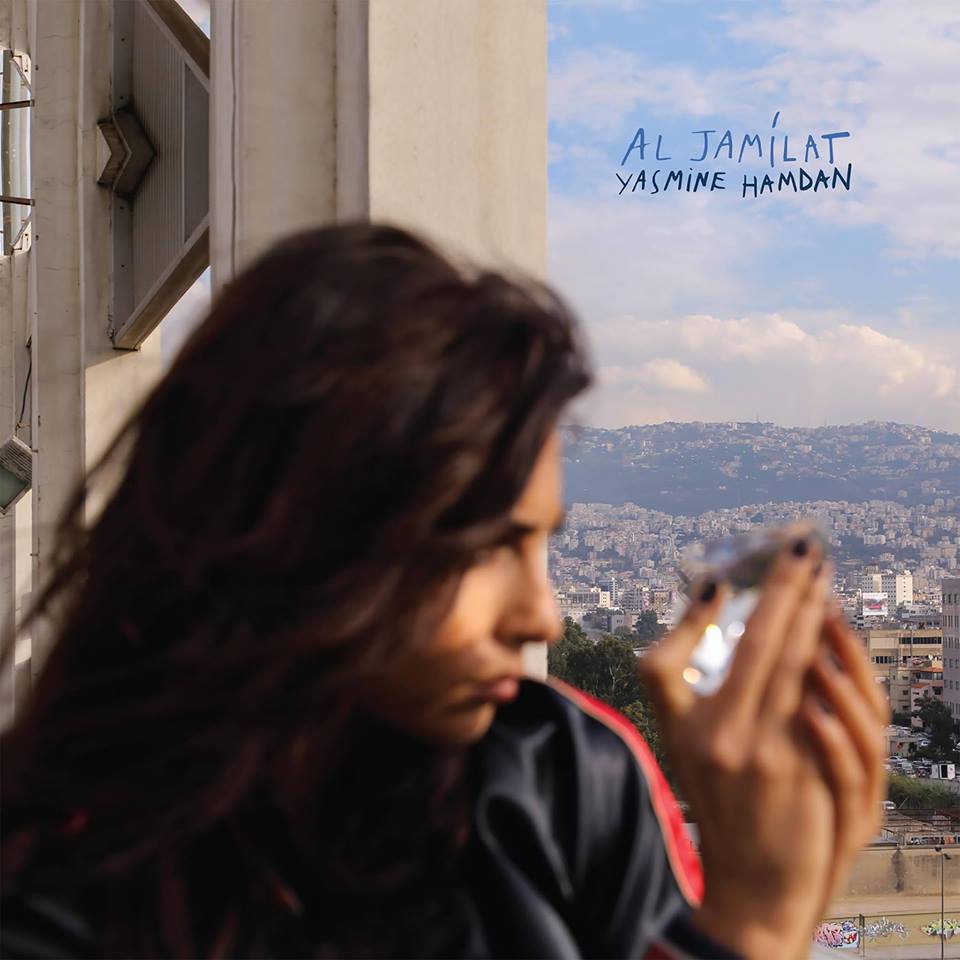

Only Lovers Left Alive, Jim Jarmusch's 2013 vampire flick, where she was performing in a Tangiers cafe. She's been hard at work since then, and is about to release a new full-length album,

Al Jamilat (out on March 31st on Ipecac Records).

Hamdan has been all over the Middle East and she currently lives in Paris with her husband, renowned filmmaker

Elia Suleiman. While in Lebanon she formed groundbreaking electro-pop band Soapkills with musician Zeid Hamdan (no relation), one of the first of its kind in the Middle East. Despite facing challenges, Soapkills created its own legacy, eventually becoming a cult group in Lebanon. In 2013, Hamdan released

Ya Nass, her first solo album (Crammed Discs).

Her new album,

Al Jamilat (which means "The Beautiful Ones"), is all about women, whose characters and stories Hamdan creates using different Arabic dialects. The title comes from a poem of the same name by Palestinian poet

Mahmoud Darwish, a gorgeous, evocative work that captures the complexity of women's experiences, something Hamdan also seeks to convey on the album. The title track is her sung rendition of the poem.

As part of an ongoing tour, Hamdan performs Saturday night at this year's

Big Ears Festival in Knoxville. I spoke with her about her new album, how singing in different Arabic dialects helps her create characters, her feelings about the state of the world right now, and more.

It's such a historical moment right now in terms of the relationship between Europe/The U.S. and the Middle East, as a kind of frenzied paranoia seems to be escalating in both areas in terms of their relationship with the other. As someone who has made a home in both worlds, how are you feeling right now? What might the way forward look like?

I'm feeling bad. I feel like it's a very complex question and situation. It's not easy to answer and there are many sides to it. I do feel very alienated by the fact that we're going backward with so many things, women's rights and so many other rights, actually. And I find that it's happening at a global scale. In so many countries, the hardcore right and anti-immigrant/anti-rights groups are on the rise. So for me, this is something that is global. It's not just coming from one place or another. It feels like it echoes in many places.

To simplify it, it's a logical result of the world we live in. There's a value crisis and an identity crisis and it's a very capitalist environment, a very consumerist environment. We live in a society where things are very fast. We don't have the space to contemplate and think about things, so maybe that is creating the problems and fears that are manifesting in what we see now. People are voting for the wrong people. And it's interesting for me to see how things are linked. If something happens in one place it's echoing in another place. That is something that I've understood lately.

In the Middle East it's a bit different. We've been in this really difficult crisis for a long time. We've had our share of pain and suffering with bad politics. Everything that's been going on for years has created a lot of problems and issues, and at the same time there are lots of battles going on more symbolically. Many people are taking part in social movements for rights, etc., but other things are crazy and going backward. It's interesting and sad, but I remain hopeful.

We are all connected. We all need to be sticking together and working together, hand in hand, but that is not at all in any agenda. Everyone's in denial of climate change and of so many things. It feels like we're just heading to a wrong place. Again, if in Middle Eastern society you are not taught to take some distance, to reflect, think, contemplate, and take action, you become a follower or a potential voter for the wrong person. So maybe this is the time to question today's systems, to question the forms of democracies we are in today. We can't avoid the fact that things are not really democratic when you are in this environment, when you vote and are manipulated. There are so many things that are not exactly ideal in our systems of democracy so maybe that is something to be reflected on. But I don't know if it's going to happen now; we're just in deep shit. We're stuck in something that is very dangerous.

A still from

A still from Only Lovers Left Alive

(dir. Jim Jarmusch, 2013).

To switch gears a bit: You've said that realizing you were a musician just kind of came to you, but when did you realize that singing and music were something you could do as a career?

I had no idea of what it meant on the ground. Maybe here in the States you have a clearer way forward. It's easy and normal that every young kid here starts a band with colleagues in school. That was not the case when I started. We started in school, but in an environment that was not at all used to that. To a certain degree, it was welcoming, but it did not at all offer any opportunities or possibilities.

When I started singing in Arabic, I became more serious because I carried the language in my head and heart. I originally started singing in English, but it was not very serious. Arabic felt more interesting and right, to sing my own way—that's when it felt like it was really what I wanted to do in my life. But it was difficult in Lebanon, and in the Middle East, to sing in Arabic, actually. It was not common, especially in underground music and culture. People looked at us, like, "What are those people doing?" It was also looked at as not classy by some people. Really! There's a lot of conservatism, and because I was not singing way Arabic should be sung, we met both open doors and some resistance. It was interesting for me. I found a drive, and I was excited, actually, to break those taboos in a way. It felt right for me to do it, not only on a career level but on a personal level, for me to just exist the way I wanted.

It was a way to resist things I felt were not good for me, to feel free as a person, a woman, and an artist. So making music my way played a big role in my life in general, and not only in my career. It was kind of a survival thing, because I didn't want to stick to the rules and I didn't care for them. I needed to free myself from them, and I was so grateful that I could do that with and through music, and share it with other people. I think that's so great. And there was also this dimension, I wouldn't say activist, exactly, but something like it, that made me feel better about what I was doing and gave me more courage, because it was not easy.

Even when we went to Europe we were confronted by, I wouldn't say discrimination exactly, but people could not put Soapkills in a box. Actually I still have the same thing come up. They don't know where to put me. I'm not really singing in Arabic. It's not world music, it's not a particular genre. I had always considered the phrase "world music" weird, because they put everyone together, and intellectually that's a big no.

Now I'm more at peace with how others categorize me, because I'm fine with anything. I move from one box to another. If you go to a shop they might put me in that box or this category, and that movement thing is really interesting. I don't mind being in any of the boxes, as long as I change from one category to another. Every time I come to a project I come up with something new. The only way for me to get excited is to go to different places and environments. So I like to shift myself.

You sing in different Arabic dialects, partly as a product of your own upbringing and all of the different places you have lived. How do you pull together these different dialects and threads of influence in your music?

For me it feels completely natural, because I lived in different Arab countries, and I can say that I also come from different places, not only Arab countries. I do feel like I have a multi-faceted identity, so I take a lot of pleasure when I sing a song in a different dialect. When I do that it's because the song needs it. Each song has its own dynamic, tempo, and groove.

I lived in the Gulf, and there's something extremely sensual and mysterious about the language for me. They love poetry, and things are not said, things are hinted. So if I want to do a song where the personality and character of the singer is a bit mysterious, she's shying away but she's also erotic or sensual, I might go for a Bedouin dialect. It really depends on the character. The Lebanese dialect is heavier, it's more slangy, it's fatty when I sing it. Egyptian is very smooth, extremely watery. It's like a little waterfall, very romantic, a bit like "drama queen." I really enjoy singing in Egyptian. Classical Arabic is the main language that normally every Arab should understand. It's the dialect we hear in the news and read in books, so it has this more pompous feel to it, more like an authority. So if a song has something more serious and dramatic it's in classical Arabic.

I just have fun with that. I really enjoy going from one dialect to another. It gives me a variety of possibility and grooves. I'm really fast with creating and composing melodies. Lyrics come to me with more difficulty, so when I find a dialect I twist it and work with it. It needs to fit the melody first. That's the priority. Because it's a question of weight and temperature. If one word doesn't work with a melody it can break the song. It's a little bit like cooking. It's a balance of things; you just need to have the right spices.

It's very organic. I feel a different environment when I sing Iraqi, or when I sing in Kuwaiti. The colors and the environment change. It's more desert; it's sandy. If I sing in Lebanese, the color changes. It's more blue.

Photo: Tani Feghali

Your new album, Al Jamilat, collects stories of women characters. Did you pull these from your or other people's real experiences, or did you create characters, or was it some of both? Is there any story that you'd like to share (real or fictional) that gives the background to one or two songs?

Photo: Tani Feghali

Your new album, Al Jamilat, collects stories of women characters. Did you pull these from your or other people's real experiences, or did you create characters, or was it some of both? Is there any story that you'd like to share (real or fictional) that gives the background to one or two songs?

When I compose I don't plan. I wait for things to come randomly, and it feels right when they fit together, that's how I see it. Many of the characters in my songs are feminine and a bit rebellious and strange. They are sometimes confused and imperfect, but they're heroes for me. They're funny and they touch me. I imagine them in one situation, and I don't keep up with them. I'm not creating a narrative. At one moment I might have a person say something. It can be very minimal, just an attitude.

The poem ("Al Jamilat") is amazingly beautiful. It's an ode to women, to femininity, imperfection, contradictions. This is how I see beauty—in imperfections and contradictions. I also feel that the poem is really positive, and we need that. We are living in a weird moment. I've always hoped and voted for rights as a woman and an artist. As a woman, I have the right to be free in any environment I've been in. That was always my big battle. And I felt in this record that I wanted to have this title and this song, and I wanted to celebrate femininity in men and women, to celebrate that aspect of beauty that I see in being imperfect, in contradiction. I wanted to compliment women, and for it to be a really positive, empowering project.

The poem is extremely beautiful, and it touched my heart. It has a lot of imagery. It has humor and tenderness. I see it as a very Middle Eastern poem. It talks about this kind of tenderness that is very local and familiar to me. It's the kind of tenderness or celebration I would have made for a woman. It's very positive and fresh. I don't know about the U.S., but in the Middle East I'm questioning a lot of things about women's rights. Of course there are battles, and people trying to change things, but we've been going backwards for years. If you watch Egyptian or Lebanese movies from the 1960s and 70s, or even earlier, the 20s or the 40s, you feel so dislocated. You're like, "Oh, what's happened? It was much more progressive and liberated." The environment was different.

What are you most excited for at Big Ears?

The performance [laughs]. And if I have the time, I hope I will be able to see other bands play. We arrive on the same day, and I might have promo, and then we have to just do the concert, but I'm excited to be there and meet people.

What's next for you?

What's next for you?

I'll be touring. I'm going back to Paris. I'm in the middle of promo, so it's very overwhelming but great. Then I have to go to Beirut and shoot a clip with my partner (Elia Suleiman). Then I will do some gigs in Budapest, and then tour in May. I'm really excited about that, about my band. We've been working really hard to put these songs together. It was kind of difficult, because when I composed and recorded them, I didn't want to put myself in any kind of context. So when we came together and wanted to work on the songs, the cycles were really weird. It was not like a 4/4 thing for some songs. Normally I just do things like I feel them, so we had to work really hard to put that together.

Then I'm taking a small break in June in Mexico, and then we'll see [laughs]. Now I just want to stop in June, but I'm excited about the fall too, about people discovering my new record. I put a lot of myself into it, and I'm really happy about it. I'm proud. And all the musicians and producers that worked with me were so much a part of making it happen.

* * *

Yasmine Hamdan plays The Standard tonight at Big Ears.

Al Jamilat comes out in the United States on March 31st.