On Friday, September 9th, tenor saxophone quartet

Battle Trance will play a show at the

Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center. The show, presented by

Free Range Asheville, is also a benefit for the BMCM+AC, and will be held at their brand new space at 69 Broadway St, across the street and down from their previous location. The show is another in a steadily lengthening list of top-notch events Free Range Asheville is bringing to our community. The admission price is on a sliding scale, with all proceeds going to the Museum. Things get started at 8 pm.

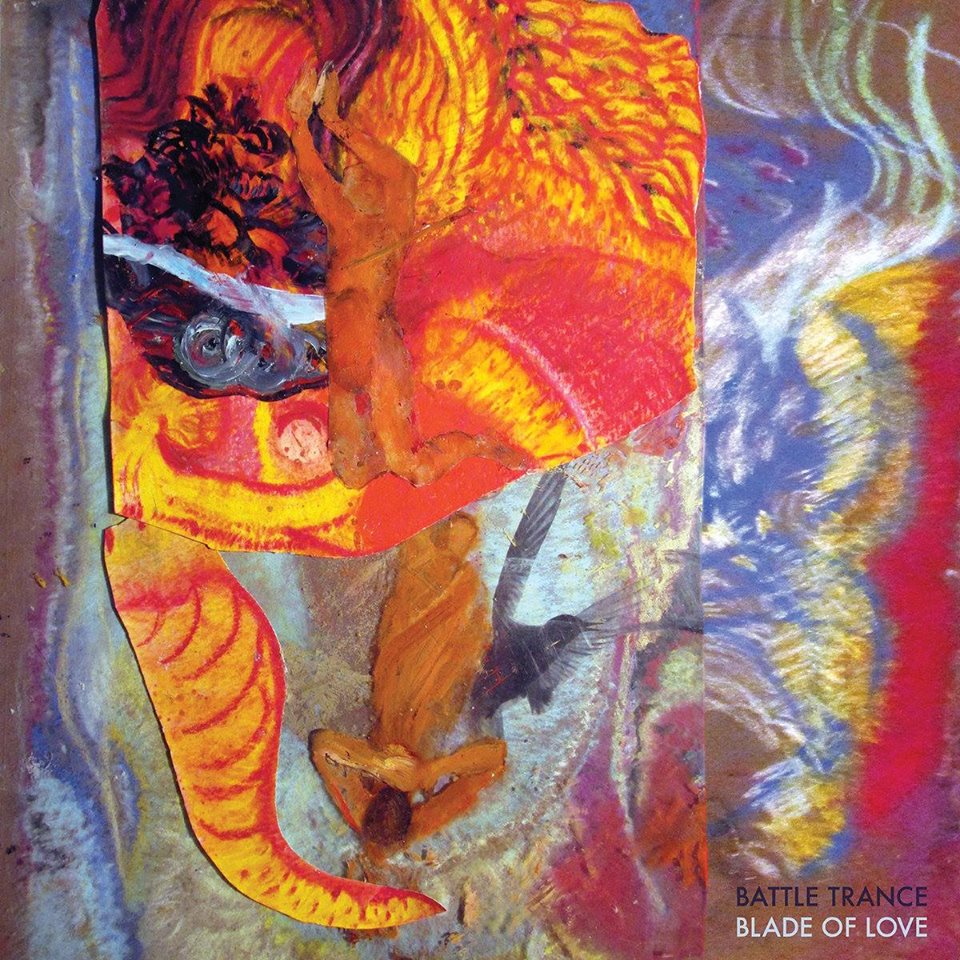

Battle Trance's music is electric, hypnotic, and, at its core, deeply spiritual. Their newest album,

Blade of Love, like their previous release, 2014's

Palace of Wind, is a single piece separated into three sections that are numbered I, II, and III. With a total running time of 40 minutes, this gorgeous album soars to arcing heights and travels down into deep, resonant, oceanic soundscapes. Sections of some pieces sound reverential and ethereal, tapping into traditions of devotional music. Other moments are guttural and strangely animal. Some sections are undefinable, existing at a threshold where harmonies come together in organic synchronicity and then fall apart just as quickly. The album also features the performers' breath as an instrument. Deep sighs, inhalations and exhalations, whistles and airy flutters become just as vital as the saxophones, adding a strange and expressive element. The record is haunting, unique, and unforgettable.

Battle Trance is founder Travis Laplante, Patrick Breiner, Matt Nelson, and Jeremy Viner. And yes, all four members play the same instrument--the

tenor saxophone. But trust me, this is saxophone like you've never heard before. Laplante was struck with the urge to reach out to the artists suddenly--in fact, he woke up one morning with the clear insight that he needed to play with these three other people (despite the fact that he was not familiar with their music). This inspired inception called together a group that has evolved into one of the most innovative I've heard.

Blade of Love was gestated over two years of intense training, composition, and rehearsal that founder Laplante calls "the most torturous and demanding compositional experience of [his] life." It was recorded "in a wooden room with soaring ceilings in the Vermont forest" (which sounds, dear readers, a bit like a church). In this space of

sanctuary, the album, which at its heart is profoundly engaged with matters of the spirit, was brought into the world. The ensemble will be performing the piece at Friday's event.

I spoke with Laplante about his own evolution as a musician, the album, and music as a spiritual practice.

Asheville Grit (AG): How did you choose the saxophone as your instrument? When and why did you start playing? How did your trajectory as a musician evolve?

Travis Laplante (TL): I was in 4th grade (10 years old), at the age when everyone's allowed to pick an instrument, and I'm not from a musical family; that is, neither of my parents are musicians. I didn't know what instrument I wanted to play. I was gravitating towards the drums because that was the coolest instrument at that age, and I remember being in the car with my mom one day--who I was and still am extremely close with--and I asked her: "What instrument should I play?"

My mom didn't have super strong opinions about music, but I remember her looking at me very directly and saying "Travis, I just love the sound of the

saxophone." And I said, "Ok mom, I'll play the saxophone." So it initially came from my connection with my mother, and from a seemingly arbitrary, small conversation that happened over the course of 30 seconds. It's great to look back on those moments in life that don't seem like a big deal at the time and become profound turning points.

I was fortunate because there was a really great saxophone teacher who lived in the same town who was also a teacher at Dartmouth, Fred Haas. I was very fortunate to start studying with him by the time I was 11. In high school, I had really supportive parents and I traveled around playing in swing bands, wearing tuxes and performing at ballroom dances. And then maybe when I was 15--I started doing this before I had a driver's license--I started to take the bus to Boston to take saxophone lessons at

Berklee College of Music and the New England Conservatory with George Garzone. My parents were on board with me taking off from school. In high school I had a job making pizzas, and I would save up and take trips to New York City during my junior and senior year, and I would try to see as much music as humanly possible in a week. Then I knew I wanted to move to NYC and did so after high school. I entered the Jazz program at New School University.

A lot transformed for me in college because I had this idea growing up that I wanted to be the "best" jazz saxophonist in the world. Coming to New York broke down a lot of illusions and veils put up for me as a teen, and I was able to see the reality behind the music scene more clearly. I didn't necessarily want to devote my life to playing music as if it were still the

1950s. I had felt that if I did anything different it would be incorrect or wrong. I learned a lot in my own journey going to conservatory, and knew I couldn't be an exclusively straight jazz player for the rest of my life.

AG: Why is the album titled

Blade of Love?

TL: When I title pieces, usually I'll just wait for the title to come to me. And most often it isn't really revealed until after the piece is complete. I just really

meditate on it, and at some point something will be given, and I think, "Ok, that's the name, the sound of that just has the resonance and is the piece."

I think the significance of this title is quite multifaceted for me personally, but it's this longing that I had, throughout the course of composing the piece, for this blade to cut through the disillusion and distractions in myself--all the things that keep me from

love all the time. It's this longing for something to take away all that is not of service to love in myself. That's more of a description of what I feel when I think about the name and why I named it that.

AG: Why did you decide to bring in the breath on this album? The saxophone--and all wind instruments--is obviously dependent on the breath. But it's the breath as employed through the instrument. What is gained by also bringing the breath into play on its own and as itself?

TL: Hopefully the listener will tell me [laughs]. When I'm writing pieces I'm really just following the sound. I'm following something in the sound into the unknown and into the mystery of what the music is becoming as I'm writing it. So it's not this conscious decision where I say, "Ok, for this next piece I'm going to use the breath." Once I'm in the feeling of it, a sound will come into my consciousness that feels like it needs to come into the piece. I will say that, in general, I feel like I've had a relatively narrow vision of what the saxophone is and is not, particularly when I was growing up, and what it is and is not capable of. And I'm just really seeking

freedom with the instrument. I'm seeking to be able to break down the intersection of when the saxophone is being played with the breath and when the breath is barely playing and when the saxophone is acting as a chamber to pass through, and the quality of timbre. I'm interested in letting things break apart more, and in not relying on using traditional saxophone tones. I do find that there's something about the breath particularly. It's that I'm trying to remember how sacred it is, how much of a gift it is to be able to take a breath and breathe.

Battle Trance

AG:

Battle Trance

AG: The album description mentions the two years you all spent working on "extended technique, both virtuosic and primal" to get ready for this record. Can you talk about what that means? Which techniques? Is there an intersection point between the virtuosic and the primal? Can you talk about both?

TL: I am a

qi gong practitioner, and in qi gong we talk about the human body having three energy centers. One is the wheel of vitality, the second is the wheel of love, and the third is the wheel of wisdom. When I think about the music that moves me the most deeply it has the charge of all three qualities--wisdom, love, and vitality--and so I don't want to make music that's doesn't have all three. I don't really care about impressing people with an unusual technique. It's in service to something more. I feel like I really don't want to abandon the fact that I have primal instincts, my lower nature and animalistic self, and having a

visceral and physical immersive quality to the music feels important. I want it to be raw and urgent and at the same time to use other techniques that take more cultivation and create different sonic environments for people that are much more precise and virtuosic--whatever word you want to use. But there needs to be a marriage of these forces for the piece to feel complete. That being said, for me what it ultimately comes down to is the heart, that's the most important thing in music and the ultimate thing for me--passing something from heart to heart.

AG: You're already speaking to this in your answers, but I'll ask more specifically. So much of your music calls up ideas of the sacred, and it's also tied into physical experience. Can you speak about the sacred elements of the music? Is music at its heart a sacred and/or spiritual practice for you and the band?

TL: Music is a spiritual practice for me, period. This could potentially become a very long conversation. I'll talk a little about my relationship to the

sacred. I am really interested in remembering something of music's original purpose, and the power of music, and I feel like throughout history music has very much been in the weave of life. Historically speaking, there wasn't such a separation between music and spiritual medicine that is invested in sound, movement, and the earth, and there's something about that that I'm really trying to remember. About how music does have a sacred root. It's something that is not just limited to the realm of entertainment for me and it's not just exclusive to a concert setting.

I am conscious that I'm not only playing to just humans. When I was in Vermont I spent time playing outdoors and being conscious of the trees, that the trees are alive, listening and responding. I can feel everything around me is alive, and I'm trying to remember something about the

relationship between humans and the earth and between humans and heaven through sound. My purpose is to stand between heaven and earth and to praise what is the most holy to me.

AG: You've said that composing this record was the most torturous and demanding compositional experience of your life. Where do you go from there?

TL: I'm really just following a sense, so to speak. I'm just definitely trying to remain in the

unknown and not think too much about what the next thing is going to be and how it's going to relate. I'm trying to just stay present to the moment in myself and on this planet in the universe, and I honestly don't really know where the sound is going to take me next, to be honest.

AG: How does the rest of the band come into the compositional process?

TL: We work very closely together, and I think it's one of the things that makes Battle Trance unique compared to many other projects. We have a very rigorous rehearsal schedule and the compositions are predominantly learned by the ensemble through the

oral tradition--through me just demonstrating everyone's parts rather than bringing in written music. I find it's more efficient and potent in terms of connecting on a deeper level. So basically I'll have a particular section of the piece, I'll bring it in, we'll workshop it, and then I'll bring in the next section and we'll carry on.

It's an amazing gift for me as a composer to have this very intimate relationship with the ensemble, because if something brought in is not working the way i was hoping, I'll know right off the bat and be able to revise it, change it, or even axe it. In a way the composition is being rehearsed as it's being written, so it's very

interactive. It's not the kind of music where I could just bring in a score to three other tenor saxophonists for them to play. It's very much a four-part ensemble and everyone is of equal importance. Without one of us it would be nothing. Everyone is vital.

AG:

AG: Who did the album artwork?

TL: I'm so glad you asked. Her name is

Priscilla Cross and she is one of my favorite living artists and human beings. She lives in Maine. I go up to Maine often because I am a student of an esoteric school called

The Unseen Hand that's located there, and that's how I met her.

AG: How did you get involved with Free Range Asheville?

TL: I played music with Jeff [Arnal, co-founder of Free Range Asheville] in New York, probably about 10 years ago, or maybe more. So I have known Jeff a long time, and then our booking manager was just trying to book our tour and worked with Jeff to bring

A Roomful of Teeth, and he just asked Jeff if he'd be up for having us and it worked out. I'm really excited to reconnect with Jeff.

--

For more information about Friday's show, you can check the event info on

BMCM+AC's website and the

Facebook event page.

Listen to

Blade of Love on

Bandcamp.